Where Did The Disappearing American Workers Go?

For weekend reading, Gary Alexander, senior writer at Navellier & Associates, offers the following commentary:

Work isn’t what it used to be, and neither are workers. Labor Day gives us time to reflect on that dirty four-letter word that made the 7 dwarves sing, and made that first “hippie,” Maynard G. Krebs, wince.

Q2 2022 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Work songs began with Disney’s first full-length film. The seven miners sang, “Dig, Dig, Dig,” dozens of times before taking up their picks and axes with a hearty, “Heigh Ho, Heigh Ho, It’s off to Work We Go.”

As a music historian and DJ, I notice that most of the great work songs have to do with mining, generally a dangerous profession that has fallen on hard times, with far fewer miners now, for several good reasons.

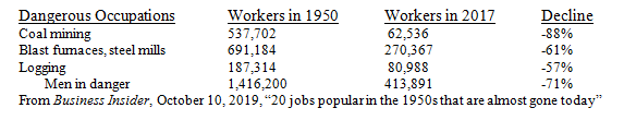

In 1950, there were over 537,700 coal miners in America, and over 100 of them usually died each year in coal mine collapses, with many of the rest dying prematurely from lung diseases.

According to CDC, in a little over a century (1900 to 2006), 513 underground mine disasters (mostly explosions and fires) killed 11,606 coal miners, an average of 110 deaths per year, mostly pre-1970. Thankfully, those jobs are now much safer and rarer, with 88% fewer coal miners, even though our workforce has tripled since 1950.

Work songs of the 1950s tended to revolve around hard labor. “John Henry was a steel driving man” was about one man’s prowess in driving nails into rails in a race against a steam-powered rock-drilling machine.

Then there was “Big John: Every morning at the mine you could see him arrive; he stood 6-foot-6 and weighed 245.” Even in the mid-1960s, “Working in the Coal Mine” became a global hit, but nothing struck a work bell louder than Tennessee Ernie Ford singing the coal-mining lament, “16 Tons.”

You load Sixteen Tons and what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt

St Peter, don’t you call me ’cause I can’t go

I owe my soul to the company store…

“16 Tons” was released on October 17, 1955. By November 10, it had sold 1,000,000 copies, the fastest million-seller in pop music history. By December 15, it had sold two million. It was #1 for eight weeks.

Who could have predicted that this dire tale of coal mine entrapment would set musical records like that? But the writer, Merle Travis, came from a long line of coal miners, so these words came from his DNA:

Some people say a man is made out of mud

A poor man’s made out of muscle and blood

Muscle and blood, skin and bones

A mind that’s weak and a back that’s strong…

Ah, but the nature of work has clearly changed since 1955…

Our New, Flexible Relationship with Work, Post-Covid

“The progressive detachment of ever-larger numbers of adult men from the reality and routines of regular paid labor poses a self-evident threat to our nation’s future prosperity.

It can only result in lower living standards, greater economic disparities, and slower economic growth than we might otherwise expect.” – Nicholas Eberstadt, “Men Without Work,” January 30, 2018

Even before COVID, there was a new relationship between work and life in America. More workers were “playing the system,” opting for early retirement at generous pension levels through government or union contracts, or gaming the disability system.

With far safer workplaces than the coal-mining era of 70 years (and 16 tons) ago, far more workers discovered bad backs or designer diseases that kept them out of work (while quadriplegic Charles Krauthammer was able to finish medical school and work at the top level of several careers without use of 90% of his body below his chest. I guess some people are wired to work.)

Once you’ve worked from home during COVID, by force of law, it’s hard to go back to the office. Of all employees, 58% now have the option to work from home at least part of the week, according to research from the management consulting firm, McKinsey, and the richer you are the more options you have, as 75% of workers making $150,000 or more have the option to work from home.

This, of course, cuts down on myriad costs – commuting time and gasoline, wardrobe costs, childcare expense, office rent and more – and it could be the “green” solution many hoped for – without the mandate of expensive electric cars.

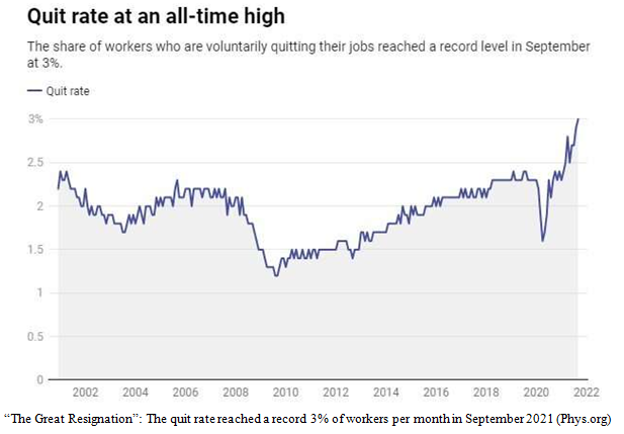

Some employers are demanding workers return to the office, and workers are either resisting or quitting, as in the World War I lament: “How you gonna keep ‘em down on the farm after they’ve seen Paree?”

Before the pandemic, I read and wrote a review of Nicholas Eberstadt’s book, “Men Without Work”. He has updated that book as “Men Without Work: Post-Pandemic Edition”, to be released September 19, and there is a preview in the weekend (September 3-4, 2022) Wall Street Journal, titled “Americans Who Never Went Back to Work After the Pandemic.”

These trends should be obvious to anyone with eyes to see, but he hangs some numbers on the obvious:

“We now face an unprecedented peacetime labor shortage, with employers practically begging for workers, while vast numbers of grown men and women sit on the sidelines of the economy – even though job applicants have more bargaining power in the ‘Great Resignation’ than at any time in recent memory. Never has work been so readily available in modern America; never have so many been uninterested in taking it.”

“Since Labor Day 2021, unfilled non-farm positions have averaged over 11 million a month. For every unemployed person in the U.S. today, there are nearly two open jobs, and the labor shortage affects every region of the country.

Major sectors are now wide open to applicants without any great skills, apart from the ability to show up to work, regularly, and on time, drug-free.” Washington politicians created massive “disincentives for work, as never before.

Padded by transfer payments, disposable income in America spiked in 2020 and 2021, reaching previously unattained heights….” Savings soared. “In 2020 and 2021, a windfall of more than $2.5 trillion in extra savings was bestowed by Washington on private households through borrowed public funds.”

The result is that “men appear to have gone into a sort of premature retirement, thanks in part to pandemic policy ‘wealth effects,’” pushing up home values and stock values.

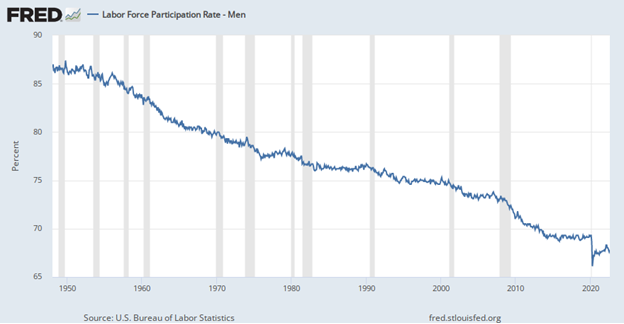

In the 1950s, men felt they had to work, so 87% of men of working age were at work or looking for work (in the Labor Force). That number is now well below 70% and still well below pre-pandemic levels:

One out of three working-age men are not in the Labor Force – the lowest rate ever. Before the pandemic, the three major reasons were: (1) skyrocketing disability claims and drug addiction; (2) lower incentives for work and higher rewards for not working; and (3) better off-the-grid options.

In a 2017 paper (“Where Have All the Workers Gone? An Inquiry Into the Decline of the US Labor Force Participation Rate”), Alan Krueger, a Princeton University economist, cited findings that nearly half of all prime working age males not in the labor force (PWAM-NILFs) “take pain medication on a daily basis, and in nearly two-thirds of these cases they take prescription pain medication,” contributing to the opioid overuse epidemic.

In another 2017 paper, titled “Declining Prime-Age Male Labor Force Participation, Why Demand- and Health-Based Explanations Are Inadequate” Scott Winship of George Mason University used an after-tax income measure, adjusted for inflation, to show that 76% of PWAM-NILFs have managed to avoid poverty since the income of the average Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) recipient just about matches the after-tax income of a full-time worker earning minimum wage.

As for the third option, there was a 67% rise in the nonparticipation rate of younger PWAMs (aged 25-34) from 1996 to 2016 since one-third were in training or school, one third had a criminal record and the other third devoted about eight hours a day to “relaxing and leisure,” like video games. They also gamble, use drugs, and watch TV a lot.

We’ve come a long way from those 16 tons of hauling coal, getting deeper in debt to the company store. There’s no need to enter a coal mine, but American men need to put their big-boy pants on and go back to work. Otherwise, the world’s harder-working, hungrier economies will eventually eclipse ours.

Source valuewalk